This blog post was originally published in Screensaver Ninja‘s blog.

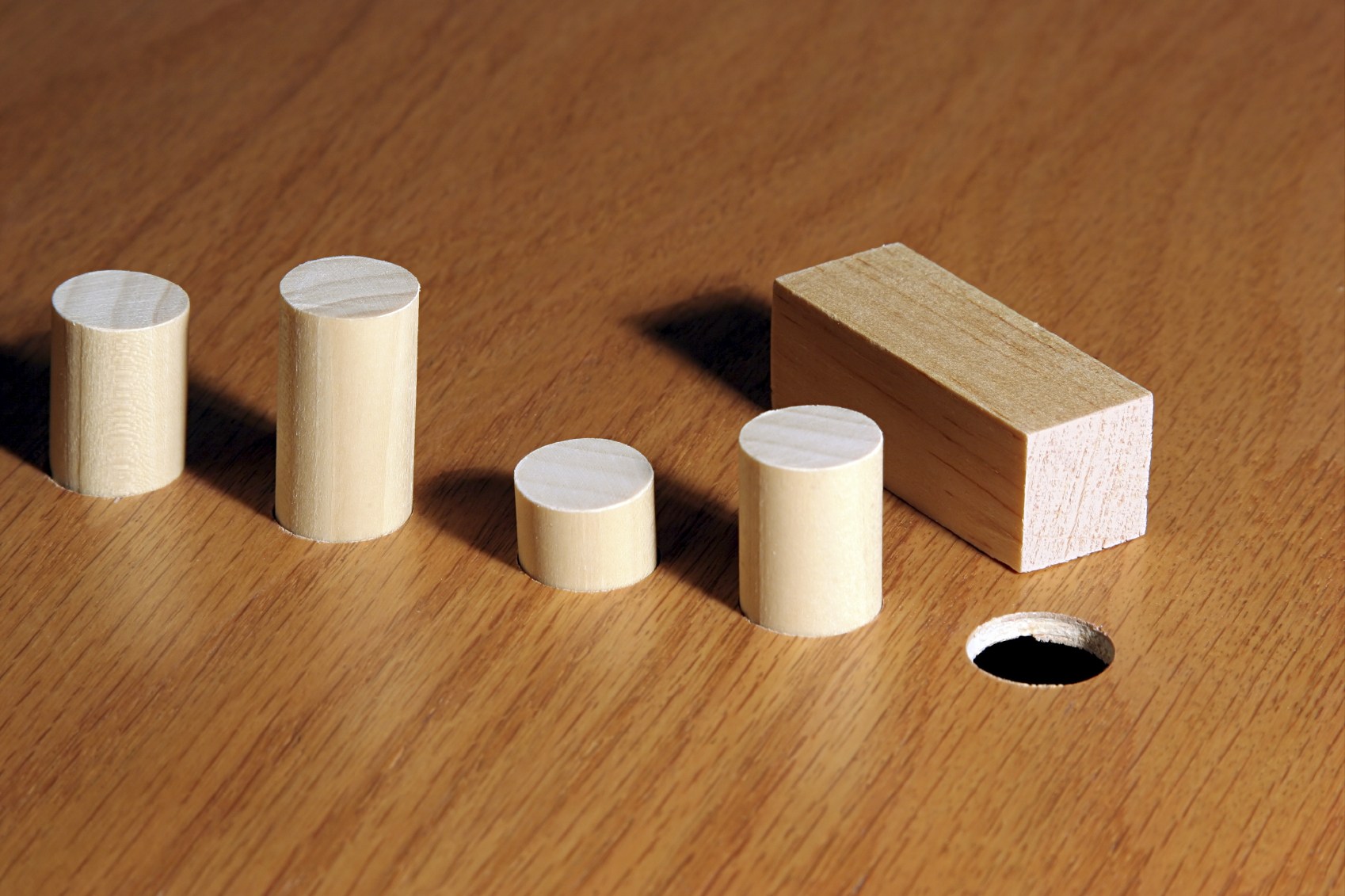

We were recently challenged by someone who asked what was so special about adding websites into a screensaver. Perhaps, at first, this doesn’t seem like a tough task but after months of challenging work, I can confirm it is. I realized I never shared exactly why yet, so here it is. Putting a browser into your screensaver is like putting a square peg in a round hole.

Chromium on Mac

Screensaver Ninja for Mac is already out there. It’s working and it’s robust, but getting there wasn’t without its pains. Initially, we wanted the Mac and Windows versions to have the exact same rendering engine and thus, we went for Chrome’s WebKit, packaged as Chromium Embedded Framework, or CEF for short.

Chromium, the open source version of Chrome, follows the same structure as Chrome to handle page isolation: by running it in different processes. On Mac, applications are distributed as bundles which you may know as .app files. They are actually directories and you can inspect the contents by right‐clicking or control‐clicking on it and then choosing Show Package Contents. (Warning: if you change anything the app will likely not work anymore.) When you use CEF, you end up with a secondary bundle application inside your application. This is sort‐of supported, but weird and not without issues.

Chromium, the open source version of Chrome, follows the same structure as Chrome to handle page isolation: by running it in different processes. On Mac, applications are distributed as bundles which you may know as .app files. They are actually directories and you can inspect the contents by right‐clicking or control‐clicking on it and then choosing Show Package Contents. (Warning: if you change anything the app will likely not work anymore.) When you use CEF, you end up with a secondary bundle application inside your application. This is sort‐of supported, but weird and not without issues.

In Mac OS X, screensavers are dynamic libraries that are loaded by a special screensaver program. When you make a screensaver, you are not in control of the running program, you just have a few entry points to start doing your animation. The Mac OS X screensaver framework doesn’t like it at all when you have a secondary app bundle that you trigger from your library.

During this research, we found a bunch of issues, many of which were not clear‐cut as solving it for us might break it for other people. We still needed those issues solved so we wrote scripts that would pre-process CEF and solve them for us. Ultimately we ended up dropping CEF; more on that later.

Swift

We decided to use Swift for our project. It’s the new way and we prefer higher level languages whenever possible. Swift saves us a bit of pain with memory management, syntax and other things. But we inadvertently caused ourselves quite a bit of pain. The Mac screensaver framework is still an Objective-C application and since we are not building an app, but a library, we need to write and compile Swift with Objective-C binary compatibility. This is not commonly done so it took us quite a bit of bumping our head against a brick wall to figure it out. Furthermore, not being in control of the program loading our library made getting error messages tricky at best.

Apple’s WebKit

When we dropped CEF, our alternative was Apple’s WebKit, which was so much easier to integrate and have running, despite the fact that there are two of them; one that works out of the box, but it’s deprecated, called WebView, and a new one that’s not so well supported, called KWWebView. We played a lot with both and both had the same problem: cookies shared with Safari.

Apple decided that all users of a web view must share cookies with Safari. This was not acceptable for us because we want to have separate independent sessions and in the future we are even planning on having separate cookie jars per site so that you can, for example, be logged in into two different Twitter accounts at the same time. We contacted Apple about it, paying our tech support fee, and the answer was a resounding “can’t be done, we’ll add it to the list of things that we’ll consider in the future”.

Challenge accepted Mr Apple! We embarked on a quest to achieve this anyway that took us into the dark innards of the Cookie Jar, debugging it at the assembly level to understand its interface and workings:

I have to admit it, that was fun. After understanding Apple’s cookie jar’s implementation, we wrote a test suite that was exercising it all, as far as we know, including bits that we believe are abandoned. After that we wrote our own implementation that stored the cookies separately and used the same test suite to make sure our implementation was equivalent to Apple’s. This code had to be done in a mix of C and Objective-C. Then we used method swizzling to replace Apple’s with our own and ta-da! Cookie separation.

Windows events

The Windows version of Screensaver Ninja is of course not done yet, but we’ve already started working on it and we are partly there. One interesting problem that we run into is that Windows doesn’t help you at all with the workflow of a screensaver. It is of paramount importance to us that while the screensaver is running, nobody should be able to interact with those websites. We don’t want any keystrokes, mouse moves, mouse clicks, etc to reach the pages, otherwise it would be a breach of our security approach to dashboards.

Windows has a long history all the way back to Windows 1.0 that ran as a little program on top of MS DOS. Awww, good old days. Through the decades, ways to code Windows applications have changed radically and thus the way events travel through applications also did. That means that there’s a lot of different ways for an app to get keystrokes, mouse events, etc. Finding them all and plugging all those holes was not trivial and since we are talking about security this required a lot of testing.

I’m sure that as we go along, we are going to find many more issues like those in the Windows environment, and we are going to solve them and we are going to strive for elegant, stable, robust code.